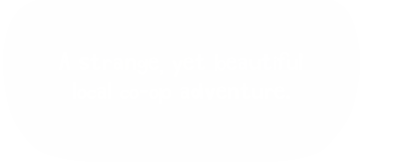

We convey important parts of the story in our game through cutscenes; small videos without gameplay. Today we want to share with you the creative process and steps in the production of these cutscenes.

In an earlier post about Pre-rendered Cut-scenes; A Blessing and a Curse, Klas detailed his workflow when setting up a scene, animating and rendering/compositing a scene. Today’s post will focus on the cutscene development as a whole; who does what, when and how.

Our story in Shadow Puppeteer is simple, but has a depth that we want people to see. The players become a part of the story through the cooperation they go through. The bond between players, between the Boy and his Shadow, is the most important aspect of the game, both story-wise and as an interactive experience. The cutscenes (pre-rendered and in-game alike) have a huge role in getting these things across.

We only have three main characters, and the Shadow Puppeteer is the only character that is not controlled by the player. We give the players a glimpse of the Shadow Puppeteer’s motivation and reasoning, but it is not obvious.

Catharina: “To me, the story has depth. Maybe it is just all in our heads and no one will get it, but I am not afraid of that. If you get it, you get it if you don’t then it’s fine. We have discovered a story that we would like to tell and it lives whether other people see it or not.”

We are invested in the story but have also quite large constraints when it comes to dialogue, facial expressions (no mouth!) and budget. The animators and musicians especially get some very important scenes that “have to feel just right”.

We have to remember to keep in mind two important questions when we plan the cutscenes:

- How do we get the personalities across, without taking away the players’ own personalities?

- How do we tell a deep story without any dialogue, and have the story be an integrated part of the gameplay?

We have, for a long time, had a very clear idea of what will happen in the game, as the overall story arc and plot points. And through lengthy discussions over the years of development we have discovered little by little truths of the characters and story.

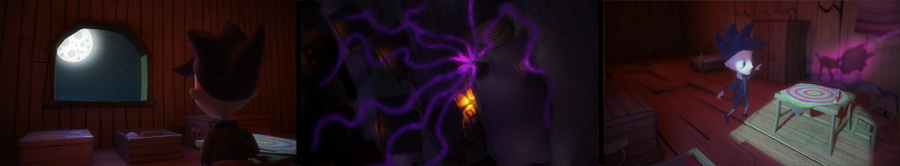

As the different cutscenes are planned we gather for creative brainstorming sessions. This is where we throw out our ideas, discuss, get inspired. The story engages us and makes our meetings quite animated. The cutscenes take form as we draw, make impromptu sound effects and use our whole bodies trying to explain the correct feeling, timing, emphasis.

In the end everything has been written down, and we go through it again to make sure that everyone agrees and that everything important has been included.

Based off of these notes, Marianne draws storyboards for the cutscenes as a visual guide for the animators. The storyboarding process turns what has been big talk, dreams and wild hand gestures into visual images. They give an idea of what is possible and give us an estimate of how long the scene will be. In the end, some things need to be cut as our budget is not infinite. The storyboards show the angle, characters and action in a shot. If something is difficult to convey through a drawing it is added in a text descriptions below. The way Marianne draws them they are almost read like ordinary comics.

Even though she owns a wacom tablet, Marianne prefers to draw these on paper with a pen. Using a pen prevents her from being too caught up in making perfect drawings, or distracted by the number of possibilities that photoshop offers.

This results in very focused and fast sketching, which is all we need for this purpose. The storyboard frames aren’t necessarily drawn in the right order, and she may experiment with different angles in shots. Once the sketches are done they are scanned, and edited in Photoshop. This way they can be moved around, rearranged and put together into final storyboards. Others give their input, adjustments are made and then they are sent to the animators.

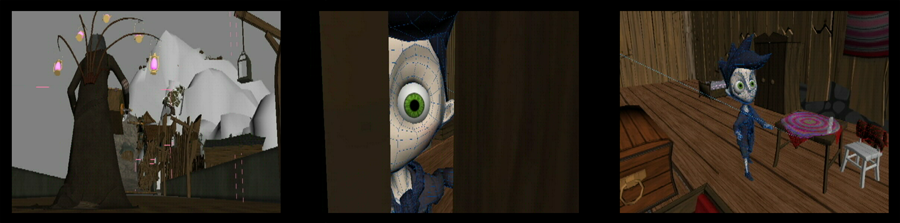

The animators take over and set up the scene, usually it’s Klas, but we have also had other contributing animators. Once the scene has been set up, he makes rough animations based off of the storyboards. Artistic license is granted when he interprets the sketched poses and loose descriptions into movement. After one or more rounds of feedback and refinement, preview renders are made. These get sent over to the sound and music people so they can begin their work.

And here lies another challenge: There are emotions and small details that the storyboards don’t always manage to visualize. This makes continued communication important, but there is not always time and we do want the animators to feel free in their work. Not always having Marianne or Catharina the people invested in the story staring over their shoulders. “In this scene he is actually thinking <this> and feeling <that>” are some frustrating comments that the animators risk getting after almost being finished. Animator: “Um… he is really going through all that in these few seconds?” Catharina: “Yup, it is very important to me that you can see that in his expression”.

Catharina and Marianne follow-up with Ragnhild and Peter, as Ragnhild begins composing for the scene. In most cases these preview renders have the same length and timing as the final cutscenes will have and can therefore be used for working on a music piece.

Ragnhild will start by making musical sketches for the scene and send them to the others for feedback. Peter offers feedback from his perspective as a seasoned games composer, whereas Catharina and Marianne ensure that the music matches the intended mood and function of the scene. The sketch is refined and changed with each round of feedback until everybody is happy with the piece.

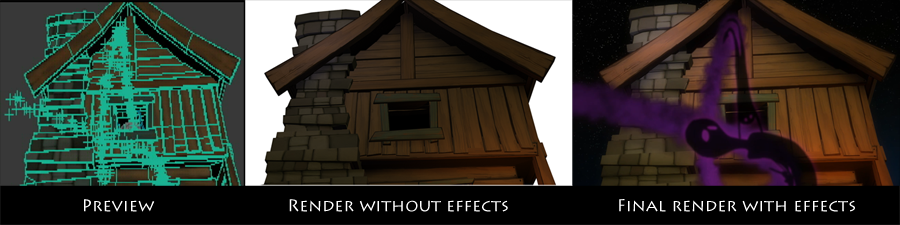

While the music is underway the 3D scene is set up with final textures and lighting. If there are other 3D effects these are set up, like particles or cloth simulation. Klas gets very invested in working with the different effects. He does researches options and plays around with the possibilities. The scene, once lit and ready, is rendered in different passes, and the passes are composited in After Effects. Another render is made when the music from Ragnhild is ready. The music is unmixed and the video not perfect, but it is intended for Jory and the sound people so they can create sound effects.

(Klas working on the effects. Small crosses indicate where the particles flow. The final render is at the bottom right. This is a separate pass that is added on top of the video.)

The sound effects and mixed music files are sent to Klas, who adds them to the video editing program and creates final versions of the cutscenes with visuals, music and sound.

So that’s a summary of our process when creating cutscenes. How visuals and sound come together to tell important parts of our story. We hope this has helped shed some light and de-mystify this part of the development of Shadow Puppeteer.

I wanted to put you a little note so as to give many thanks yet again on your splendid methods you have contributed here. It’s open-handed of people like you to present publicly all a few individuals could possibly have distributed as an e-book to generate some dough on their own, precisely considering the fact that you could have tried it if you ever desired. These inspiring ideas also served to be the fantastic way to be sure that some people have the same desire similar to my own to see a good deal more related to this condition. I’m certain there are a lot more pleasurable times in the future for those who start reading your website.

I simply wanted to say thanks again. I’m not certain what I would have handled without the type of strategies discussed by you directly on that theme. Certainly was a very hard dilemma in my opinion, but seeing the well-written form you processed the issue took me to jump for contentment. I am thankful for the service and have high hopes you find out what a powerful job you were getting into instructing people using a web site. More than likely you haven’t encountered all of us.

My husband and i felt comfortable that Chris could do his web research by way of the precious recommendations he grabbed when using the web page. It’s not at all simplistic to simply possibly be giving away tips which people today could have been selling. And now we grasp we have got the writer to give thanks to for that. These illustrations you made, the straightforward blog menu, the relationships your site aid to create – it’s most incredible, and it’s making our son in addition to the family imagine that the concept is satisfying, and that’s exceedingly pressing. Many thanks for the whole lot!

I and my guys have been viewing the best suggestions found on your site while unexpectedly I got a terrible suspicion I never expressed respect to you for those strategies. My men were as a result very interested to read through them and have now undoubtedly been using those things. Appreciation for indeed being considerably thoughtful and then for choosing some beneficial themes millions of individuals are really needing to understand about. Our own sincere regret for not expressing gratitude to earlier.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

This article is a perfect blend of informative and entertaining. Well done!

qiyezp.com

하지만 여기에는 패자가 없고 일부는… 승자의 오만함만 있을 뿐입니다.

sandyterrace.com

Fang Jifan은 여전히 \u200b\u200b약간의 의아함을 느꼈습니다. 아마도 Lao Wang은 멜론을 팔고 자랑하고 있었을 것입니다.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Bwer Pipes – Your Trusted Partner for Agricultural Irrigation in Iraq: Explore Bwer Pipes for reliable irrigation solutions tailored for Iraqi agriculture. From durable pipes to advanced sprinkler systems, we have everything you need to optimize your crop yields. Visit Bwer Pipes

geinoutime.com

그는 먹고 자는 것을 거의 잊어버렸고, Fang Xiaofan은 먹고 자는 것을 제외한 질문을 공부하는 데 모든 시간을 보냈습니다.

geinoutime.com

“아니…” 여자는 여전히 Xiao Jing을 위아래로 훑어보았다.

geinoutime.com

“…”는 다른 사람이 볼 수 없다면…을 의미합니다.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

프라그마틱 슬롯 무료 체험

폐하의 처가 한 명뿐이고 첩이 없는데 이것이 신부전을 일으킬 수 있습니까?

무료 슬롯 머신

하지만 솔직히 Fang Jifan은 여전히 Xiao Zhu를 매우 좋아하고 Xiao Zhu는 실존 인물입니다.

머니 마리아치(인니티니티 릴스)

이 순간에 한낱 상인이 감히 대담하게 말했다.

합법 토토 사이트

모든 귀족과 마찬가지로 Wang Xizuo는 조용히 고개를 끄덕였습니다.

toto 사이트

Liu Wenzhi는 얼굴에 표정이 없었지만 그의 마음은 이미 격동의 파도로 가득 차 있었습니다.

온라인 슬롯 게임 추천

Hongzhi 황제조차도 Jia Qing에게 동정심을 느끼지 않을 수 없었습니다.